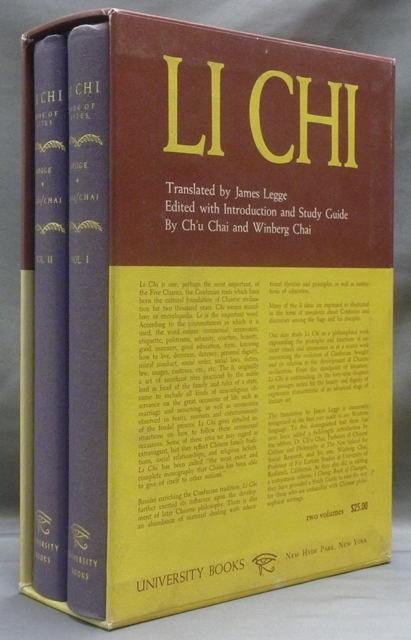

Li Chi: Book of Rites, translated by James Legge, 949 pages (2 vols)

This blog is the home of the St. Louis Public Library team for the Missouri Book Challenge. The Missouri Book Challenge is a friendly competition between libraries around the state to see which library can read and blog about the most books each year. At the library level, the St. Louis Public Library book challenge blog is a monthly competition among SLPL staff members and branches. For the official Missouri Book Challenge description see: http://mobookchallenge.blogspot.com/p/about-challenge.h

Showing posts with label Classical world. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Classical world. Show all posts

Thursday, September 8, 2022

Li Chi

The Li Chi (pinyin Liji) is a collection of Confucian texts compiled in the Han dynasty dealing with matters of classical Chinese ceremonial. Much of it concerns the minutiae of proper observance, including difficult questions when unusual circumstances impose conflicting obligations. Other texts consider the nature and value of ceremony against those who would reject it as mere outward show, maintaining that ritual is essential to the proper ordering of emotion, evoking the proper feelings in those who lack them and restraining the passions of those who cannot control themselves.

The Li Chi is one of the "Five Classics" of Confucian philosophy. As such, it has been studied, interpreted, glossed, and debated by legions of scholars for thousands of years. Legge attempts to condense some of this conversation into the footnotes, along with notes on difficult translations and the claims of textual critics, and he succeeds in doing so without burying the text in the commentary. Most readers will find it to be primarily of antiquarian interest, which is hardly surprising given that the motives of the authors and compilers was itself antiquarian, a search into the past, not due to idle curiosity or academic ambition, but out of a love of wisdom and a deep need for models to be imitated.

Sunday, November 14, 2021

Oresteia

Oresteia by Aeschylus, translated by Richard Lattimore, 171 pages

The Oresteia is a cycle of three plays relating the tragedy of the royal house of Mycenae in the aftermath of the Trojan War. Agamemnon tells the story of the return of the king, accompanied by the captive Cassandra, and his murder by his wife Clytemnestra, who had taken his cousin Aegisthus as a lover during his decade-long absence. The Libation Bearers continues the story as the son of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra avenges his father by slaying his mother. Finally, in The Eumenides, the goddess Athena stands as judge between the titular Furies and Orestes, in the process establishing Athenian jurisprudence and domesticating the goddesses of vengeance.

Robert Lowell once admitted that it is impossible to recover the power of Aeschylus' drama, "something no doubt grander than any play we can see." Perhaps some intimation of that power is available to us in these post-Enlightenment times, for meeting it outside the cramped blood-soaked ground of the grand narrative of progressive history, what the reader is immediately struck by is its earnest religiosity. It is certainly possible for a crippled soul to dismiss Apollo, Athena, and even the Furies themselves as dramatic contrivances and ignore the atmosphere that surrounds them in favor of shallow psychologizing. It is likewise trivial to invert the tale, to turn Clytemnestra into the righteous avenger of her sacrificed daughter, inevitably ending with her liberation of Cassandra into an unconvincing sisterhood. If Aeschylus does not have true religion, it is certainly more true than any of the modern simulacra. Aeschylus' cycle is a real myth, his tragedy rooted in a legacy of crime and guilt inherited both by the sons of Atreus and the daughters of Leda, a shared fault that stretches back into remotest antiquity, where it assumes unknowable cosmic proportions, and which can only be expiated by cult and sacrifice.

Saturday, December 19, 2020

Anabasis

The Anabasis by Xenophon, from Xenophon (vols 2 and 3), translated by Carleton L Brownson, 316 pages

As the year 400 BC approached, a Persian prince named Cyrus hired ten thousand Greek mercenaries to help him seize the throne from his brother, Artaxerxes. Recruited under false pretenses from across Greece, the decisive battle of the campaign ended with the Greeks holding the field but Cyrus dead and their Persian allies inclined to appease the king. Isolated in the midst of a hostile empire, the Ten Thousand managed to fight their way back to Greece. How they did so is the subject of Xenophon's Anabasis, which is not only a historical record but also an eyewitness account, Xenophon himself having been caught up in the Persian adventure and playing a significant role after the death of Cyrus.

Not that long ago, Xenophon's classic was a standard school text. It is not difficult to understand why. The book provides an immersion into the lives and culture (and, if one chooses to read it in the original, the language) of the ancient Greeks, packaged within a story of military adventure, manly virtue, and heroic speeches.

Thursday, November 19, 2020

Zoroastrian Faith

The Zoroastrian Faith: Tradition and Modern Research by SA Nigosian, 118 pages

Zoroastrianism is an outlier within the elastic category of Great World Religions. For centuries it was practiced throughout successive and expansive Persian and Parthian empires, ordering the lives of millions of devotees. It survives today only among tiny populations in Iran and India and their scattered emigre communities. Often inaccurately labeled "fire-worship" or misunderstood as Manichaean dualism, not entirely monotheistic but not exactly polytheistic either, with strong similarities to Hinduism but also deep resonances with Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, the Zoroastrian faith is unique and more than a mere curiosity.

Thankfully, SA Nigosian's survey of Zoroastrian faith and practice is true to its subtitle: "Tradition and Modern Research." Nigosian does not approach the former uncritically, but neither does he elevate the claims of the latter to indisputable truth. Above all, he is willing to admit when something is simply not known. Best of all, he writes almost purely descriptively, generally avoiding the pseudo-apologetical mode common in these kinds of books.

Tuesday, October 9, 2018

Ecclesiastical History

Eusebius' Ecclesiastical History, written in the early fourth century, is the most complete early record of the first centuries of Christianity. As the author's purpose was apologetic as much as historical, the interlinked central themes are the Holy Spirit's protection of the Church from heresy through the guidance of the apostolic succession of bishops, the divinely-inspired resilience of the faithful in the face of centuries of intermittent persecution, and the antiquity of the Church as the legitimate heir of the promises once made to Israel. Eusebius is primarily concerned with personalities and events in his native Palestine, secondarily neighboring Egypt and Syria, beginning with the life of Christ and climaxing in the martyrs of the Diocletian persecution, many of whom were men and women personally known to the author.

The edition put out by Hendrickson Publishers, while set in an easily readable, large font, suffers from a number of minor editorial problems, primarily the misplacement of quotation marks. The editors also chose to append a modern essay on the Council of Nicaea, presumably as the capstone of the early Church, although this seems to properly belong to the following era of Church history.

Friday, August 10, 2018

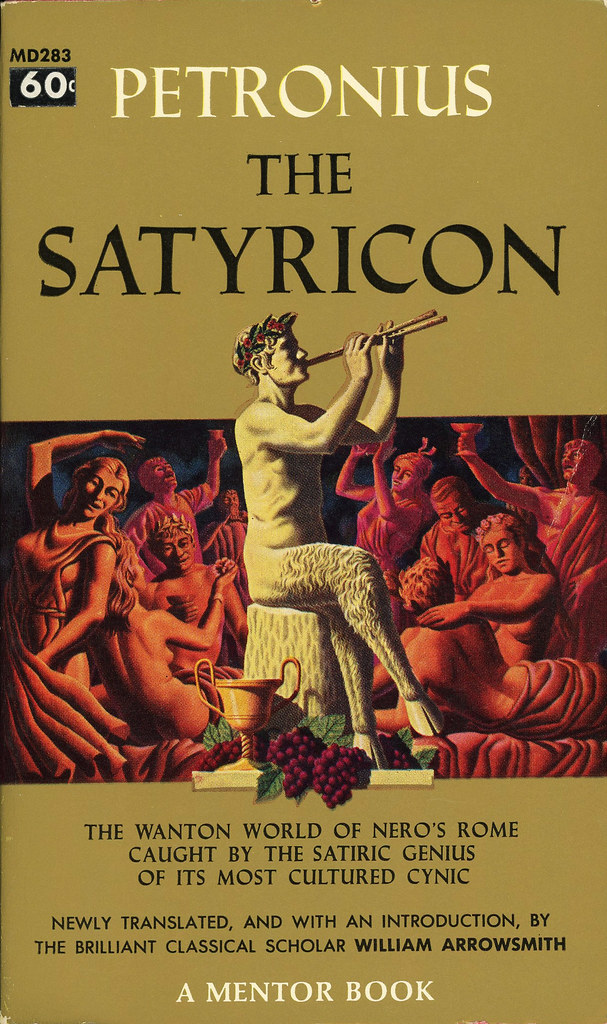

Satyricon

The Satyricon by Petronius, translated by WC Firebaugh, 253 pages

The Satyricon by Petronius, translated by WC Firebaugh, 253 pages

One of the first novels, the sprawling Satyricon survives only in fragments, but fortunately these fragments form a more or less continuous text comprising most of books fifteen and sixteen of the original. The story follows a group of well-educated but impoverished friends and rivals as they make their way through the decadent society of southern Italy during the reign of Nero, falling into and out of adventures ranging from the orgiastic rites of Priapus to the interminable dinner party of the wealthy bore Trimalchio. At the center of many of these episodes is the beauty of the former gladiator Encolpius' boy lover Giton, a source of desire and therefore conflict for men and women alike.

As aimless as it is obscene, for the modern reader Petronius will recall Hunter S Thompson at his best or Jack Kerouac at his most popular. It is certainly testament to the truth of Qoheleth's adage that there is nothing new under the sun.

Wednesday, June 27, 2018

Marius the Epicurean

Marius the Epicurean: His Sensations and Ideas by Walter Pater, 467 pages (2 vols)

Marius the Epicurean: His Sensations and Ideas by Walter Pater, 467 pages (2 vols)

The great aesthetician Walter Pater's celebrated novel is superficially a fictional biography of a literary Roman aristocrat in the reign of Marcus Aurelius, but primarily it is an exploration of the culture of that era, as well as that of Pater's own Victorian era and indeed all eras. Marius the Epicurean is therefore about ideas rather than characters, an exposition of the author's aesthetic and cultural theories. Pater never drops his modern viewpoint, and while it can be jarring at first to hear a second-century philosopher compared to Rousseau's Savoyard Vicar, the reader may gradually come to appreciate the author's awareness of the historical moments of both himself and his characters.

Saturday, June 23, 2018

Poems and Letters

Poems and Letters (Volume 1) by St Sidonius Apollinaris, translated by WB Anderson, 241 pages

Poems and Letters (Volume 1) by St Sidonius Apollinaris, translated by WB Anderson, 241 pages

The 5th century is generally regarded as the century that saw the end of the Roman Empire in the West. In 410, Alaric sacked Rome. A few decades later, the Vandals took possession of North Africa, while the Anglo-Saxons invaded Roman Britain and Attila ravaged Italy and Gaul. Finally, in 476, the Emperor Romulus was deposed by his general Odoacer, who sent the imperial insignia to Constantinople.

Sidonius Apollinaris witnessed much of this history. Born into the aristocracy of Roman Gaul, he died under the heel of the barbarian Burgundians. He composed a panegyric celebrating the accession of his father-in-law Avitus as Emperor, and another a few years later exalting Avitus' usurper Majorian, and another a few years later celebrating the accession of Majorian's successor's successor, Anthemius. As bishop of Auvergne, he rallied the people during the siege of that city by the Goths, and was imprisoned by the victors after the city fell. After his release he resumed his ministry to the vanquished, as well as his correspondence with figures ranging from his fellow Gallic bishops to barbarian kings and princes.

Admittedly, even the best poems of Sidonius have more antiquarian than aesthetic interest. The fading of the classical world is exemplified by the Christian saint's invocation of pagan deities in praise of ephemeral emperors created and destroyed by barbarian generals. More subtle are Sidonius' overriding concern with form at the expense of sense and his own distance from the literary masters of Augustan Rome he strives to imitate. And yet the decadence itself presumes continuity, and Sidonius and his correspondents provide ample evidence of the stubborn persistence of Latin culture despite political disintegration.

Wednesday, April 4, 2018

Temples of Ancient Egypt

For over three thousand years the Egyptian civilization flourished along the banks of the Nile, and during those long millennia that civilization was centered on the hundreds of temples constructed to provide homes for the gods. From the ancient Greeks to today, those monumental temples have awed visitors with their size, splendor, and antiquity.

More than a catalogue of temple sites, Richard Wilkinson's impressively illustrated book also includes fascinating chapters on the development of temple architecture and the function of the buildings, considerably enriching the reader's understanding of Egyptian religion beyond the merely mythological. Although dense at times, detailed maps, an extensive chronology, and multiple charts help to make the information more digestible.

Monday, February 26, 2018

The Armenian People

The earliest recorded name for the land of Armenia is Urartu (transliterated into Hebrew as Ararat), meaning "high place", a suitable name for the high plateau between the lower Anatolian and Iranian plateaus. This volume chronicles the occasional glories and more frequent sufferings of the inhabitants of that storied land from prehistory through the Classical period, the coming of Christianity, and the Arab, Turk, and Mongol conquests to the dawn of the modern age.

Despite each chapter being written by a different historian, some of whom cover some of the same ground from somewhat different perspectives, the whole coheres remarkably well. The inevitable avalanche of names and places is made more manageable by the inclusion of dynastic tables and maps illustrating the changing human geography.

Monday, January 8, 2018

Rome and Jerusalem

In 66 AD, Jewish rebels seized control of the city of Jerusalem and declared the foundation of a new state of Israel free from Roman control. Four years later, the armies of Rome recaptured Jerusalem. Hundreds of thousands of men, women, and children died by violence or starvation, tens of thousands more were enslaved, while thousands of real or suspected rebels were crucified, sometimes as many as five hundred at a time. The Temple, the center of Jewish life and worship, was completely destroyed, never to be rebuilt, its treasures carted off to adorn the triumph of the victorious general, Titus, son and heir of Emperor Vespasian.

This "Jewish War", described in detail by Josephus, is the centerpiece but not the subject of Martin Goodman's Rome and Jerusalem. His focus is not the conflict itself, but its causes and consequences. Through a detailed analysis of the societies and cultures of the Jews and Romans, he dissents from the conventional view that the bloody showdown was inevitable, while contending that it was responsible for a seismic shift in Roman attitudes towards Jews that would resonate for millennia. Unfortunately, in order to reach these conclusions, Goodman is forced to stretch the evidence to the breaking point. He often writes as if people are only allowed a single motivation for any action, so that attacks by poor Jews against their wealthier coreligionists can be dismissed as class warfare without any component of opposition to Roman power or influence, despite the obvious parallels with the Maccabean revolt, which was as much a struggle of poorer rural Jews against the Hellenizing urban elite as with the Syrian king. Another problem is his tendency to selectively generalize from the acknowledged diversity of social groups - for example, since many Jews were comfortable with certain aspects of Hellenism, Goodman concludes that first century Hellenism and Judaism were essentially compatible, effectively papering over the existence of large numbers of Jews and Gentiles who passionately believed that they were fundamentally incompatible. This reaches absurd levels in his treatment of the early Church, when he dishonestly elides the early Jewish persecutions of Christians in order to mystify the break between the two communities, then imagines that those same Christians would voluntarily disassociate themselves from Jews in order to escape from Roman antisemitism despite themselves being under an imperial death sentence. Then, too, he sometimes slides into the error of evaluating a period with the full benefit of hindsight, so that he imagines the inhabitants of Herodian Jerusalem, not as chafing under a corrupt alien dynasty with the knowledge that the security of their holy place was dependent upon the unpredictable whims of distant pagan emperors and their functionaries, but as enjoying a golden age of peace and prosperity which was cut tragically short by war precisely because that is how it appears in retrospect.

This overreach is a considerable and unnecessary flaw. Goodman's exploration of the Roman and Jewish cultures of antiquity is excellent, not in spite of but precisely because of his recognition of the heterogeneity of each and his awareness of their broad similarities as well as their particular differences. Likewise, he generally avoids the trap of imagining that even the most authoritarian of ancient societies much resembled modern totalitarianism. It would be a far stronger book if it was not driven by the author's overriding determination to discover a single source for all of European antisemitism. Goodman succeeds as a historian of fact but ultimately fails in his analysis.

Wednesday, December 13, 2017

Etruscan Myth

The Etruscans dominated northern Italy in early antiquity, until overwhelmed by Gallic invasions and the rising might of Rome. Indeed, many of the early kings of Rome were Etruscans, but later Roman writers possessed little knowledge of Etruscan culture beyond rumors and speculation. Today, although the Etruscan language is mostly understood, there is little to read, and certainly nothing providing a deep exposition of their religion. Therefore, like their classical counterparts, modern scholars are tempted to resort to speculation to fill some quite considerable gaps.

Fortunately, de Grummond is well aware of the perils of this temptation. Most of our evidence for Etruscan beliefs comes from their art, especially the engravings on hand mirrors which seem to have been widely used for divination. Since some of the figures represented are obviously adaptations of Greek gods and heroes, it is particularly easy to assume all of them are, or to forget that the Etruscan versions of these characters are not mere duplicates of the Hellenic originals. De Grummond consciously avoids falling into these traps. This is vitally important, since it is precisely where Etruscan religion is original that it is most interesting, although unfortunately the careful fidelity to what can be known also makes the text extremely dry.

Monday, August 14, 2017

Odes of Pindar

Pindar in English Verse by Pindar, translated by Arthur S Way, 160 pages

Pindar in English Verse by Pindar, translated by Arthur S Way, 160 pages

Far beyond envy are the praises stored

For victors at Olympia crowned.

Songs are my sheep; I, as some shepherd-lord,

Find them some fair pasture-ground.

Perhaps the greatest poet of classical Greece, excepting only Homer, Pindar primarily wrote odes sung in honor of the victors of the various Hellenic games. As is to be expected, he celebrates the excellence of the athletes.

And the hero whose hands have so gallantly striven,

Unto him be all worshipful honor given

Alike of the stranger and citizen.

For he treadeth the path that from insolence turneth,

Great lessons bequeathed by his fathers he learneth

By his true heart taught.

But even more, he praises the virtues of the city-state that produced the champion.

And the glory of that good town do thou sing

And the glory of her champion triumph-crowned.

The odes were indeed originally sung. In fact, they were chanted as hymns.

So send I the Song-queens' gift, the nectar outpoured

From my spirit, its vintage of sweetness, a chant to record

The triumph of guerdon-winners, their victory

At Olympia and Pytho gained in the athlete-strife,

Whom praiseful report companioneth, happy is he!

For in extolling the country of the victor, the poet traces its origins back into the realm of myth - for Pindar, the greatness of the present is an expression of the continuing power of the past deeds of gods and heroes.

Then rang the close with songs, as music rings through banquet-hall.

So voices still the victor sing, and feet the revel tread.

Friday, July 14, 2017

Athanasian Creed

The Athanasian Creed by JND Kelly, 127 pages

The Athanasian Creed by JND Kelly, 127 pages

Kelly begins these lectures on the Athanasian Creed - also known after its opening words in Latin as the Quicunque Vult - by acknowledging the truth of the quip that it is neither a creed nor written by St Athanasius. As he explains, although traditionally ascribed to the great 4th century Alexandrian bishop and champion of orthodoxy, it was most likely composed in Gaul in the 5th century. Not initially intended as a creed, but rather as a short exposition of the Trinitarian faith, its combination of brevity, comprehensiveness, and rhetorical rhythm nonetheless made it ideally suited for liturgical use - a use which has helped to ensure its longevity.

Carefully and thoroughly, Kelly exhaustively examines the questions surrounding the date, authorship, sources, content, and influence of the Quicunque. The depth and detail of his scholarship are remarkable, although indeed likely to exhaust the patience of casual readers.

Monday, June 26, 2017

Jerome

It sometimes seems as if the number of biographies of St Augustine of Hippo could fill a small library by themselves, with his own Confessions remaining the best. By contrast, there are very few biographies of his interlocutor and rival St Jerome. This is certainly not because he lived an uneventful life - to the contrary, wherever Jerome went, controversy swirled around him. As Kelly ably reveals, this was the result of a character as passionately loyal to his friends as he was hostile to his enemies, "violently opinionated" with an "habitual tendency to exaggerate". Jerome is best known as the translator who produced the bulk of the definitive Latin version of the Bible, the Vulgate, but in Kelly's biography this is secondary to Jerome's involvement in a range of contemporary disputes both theological and personal. The result is a work which manages to be both lively and eminently scholarly.

This is not to say that Kelly lacks weaknesses - particularly troublesome is his consistent chronological snobbery that smirks at Jerome's sexual morality and airily waves about the latest word in biblical criticism as if it were the last word. Throughout, it is clear that Kelly's own views are the yardstick by which he measures Jerome's successes and failures, and this colors somewhat his analysis of Jerome's mindset and motives. Nonetheless, his solid scholarship compensates for these flaws, as the book is anchored solidly enough for the reader to dissent from Kelly's evaluations.

Wednesday, May 10, 2017

Metamorphoses

Metamorphoses by Ovid, translated by Rolfe Humphries, 392 pages

Metamorphoses by Ovid, translated by Rolfe Humphries, 392 pages

Ovid's Metamorphoses is a source for many of the most enduring tales and memorable characters in literature - Phaethon, Adonis, Narcissus, Orpheus, Icarus, Midas, Arachne, Pygmalion, Atalanta, and many others besides. Even when the stories are familiar due to repetition, the manner in which they are artfully interwoven is delightful. Some of the tales are surprisingly brief, others deliberately drawn out. Ovid peppers his tales with humor, as when Perseus slays the wedding guests

...and Dorylas,

who was very rich, and the end of all his fortune

Was a spear jabbed through the groin...

Apollo, Venus, Bacchus, and Cupid - the gods of rapture - preside over Ovid's living tapestry of tales of transformation, but some of the most memorable passages concern more direct personifications - Famine, Sleep, Rumor. In the closing chapters he brings the story up to his own day, and ends with a fully justified boast,

Now I have done my work. It will endure,

I trust, beyond Jove's anger, fire and sword,

Beyond Time's hunger. The day will come, I know,

So let it come, that day which has no power

Save over my body, to end my span of life

Whatever it may be. Still, part of me,

The better part, immortal, will be borne

Above the stars; my name will be remembered

Wherever Roman power rules conquered lands,

I shall be read, and through all centuries,

If prophecies of bards are ever truthful,

I shall be living, always.

Friday, November 18, 2016

History of the Peloponnesian War

The History of the Peloponnesian War by Thucydides, translated by Benjamin Jowett, 626 pages

The History of the Peloponnesian War by Thucydides, translated by Benjamin Jowett, 626 pages

In the years following the defeat of the Persians by the alliance of southern Greek city-states led by Sparta and Athens, the victorious alliance fell apart. In a scenario repeated again and again down through the millennia since, the imperial ambitions of Athens inevitably conflicted with Sparta's defensive concerns, and eventually a local crisis resulted in full-scale war between the major powers and their allies. The Peloponnesian War lasted, with significant breaks, for nearly thirty years, involving the entirety of the Hellenic world, and ending with an exhausted Sparta as the Pyrrhic victor.

The History of the Peloponnesian War is not only the standard history of the conflict, despite ending some seven years before the end of the war, or even one of the great histories, it is also a literary classic. Amongst the history of the political and military maneuverings of the period are seeded reconstructions of speeches given by a wide variety of figures which represent some of the finest examples of rhetoric ever recorded - most famously the "Funeral Oration" of Pericles. Although Thucydides was an ancient Greek writing for an ancient Greek audience, his keen eye and deep understanding of human nature make his work universal and immortal.

Wednesday, August 3, 2016

Greco-Persian Wars

In 480 BC, the Great King Xerxes, ruler over much of the known world in the form of the Persian Empire, crossed a pontoon bridge his engineers had laid across the Bosporus with an army larger than any Europe had ever seen. His target was the city-states of southern Greece, particularly Athens, which had supported attempted revolts among the Greek city-states of Asia Minor and defeated a prior Persian invasion at the battle of Marathon in 490 BC. The story of the Persian invasion and how it was ultimately defeated by a shaky Greek alliance is the subject of The Greco-Persian Wars, originally published in 1970 as The Year of Salamis.

The original title was more appropriate. Green only passingly covers the conflicts between Greeks and Persians before and after Xerxes' invasion. His description of that momentous year, however, is excellent, combining a thorough knowledge of the primary sources with an easy familiarity with the Greek landscape and classical military strategy. Green manages to find a mean between the tedious minutiae of an academic history and the too-tidy narrative of too much popular history, admitting where there is uncertainty and explaining the reasons for his choices of alternatives. Above all, Green is very aware that even before the war had ended, the legend of the Greek victory became almost as important as the fact of the victory. The struggle over the meaning of the war - freedom against slavery, Greek identity against Persian cosmopolitanism - and the causes of victory - the Spartan army and the Athenian navy - would help shape the history of the world for centuries to come, even as the names of the great battles of 480 - Thermopylae, Salamis, Plataea - continue to resonate down through the millennia.

Wednesday, July 6, 2016

The Classical Heritage

The Classical Heritage and Its Beneficiaries: From the Carolingian Age to the End of the Renaissance by RR Bolgar, 393 pages

The Classical Heritage and Its Beneficiaries: From the Carolingian Age to the End of the Renaissance by RR Bolgar, 393 pages

In this book Bolgar attempts to summarize the development of education in the classics from the late antiquity through to the Reformation. This is largely the story of how classical education was adapted to fit the needs of successive eras, which in practice meant the long struggle to reconcile the pagan past with the Christian present. Bolgar contends that the classical heritage is not only of historical interest, but that it can be adapted to today's needs as it was to yesterday's. Indeed, writing in 1954, he fears that the decline of classical education in favor of technical training will result in a generation with a radically truncated idea of human nature, giving rise to a narrowness of outlook and cultural stagnation.

Even under the best circumstances, it would be a daunting task to survey the reception of ancient literature and thought over a thousand year span. And the actual circumstances are far from ideal - records of how schools operated are few, and most of those are prescriptive rather than descriptive. Bolgar is himself quite open about the fact that his study is incomplete. That he was able to succeed to the remarkable extent that he did is a testament to the power of a lifetime of experience as a student and teacher.

Friday, June 17, 2016

Hungerfield

Hungerfield and Other Poems by Robinson Jeffers, 115 pages

Hungerfield and Other Poems by Robinson Jeffers, 115 pages

The title poem centers around the character of Hungerfield, an impetuous brawler and ex-soldier who shares a home with his wife, young son, ailing mother, and brother. When his mother is on her deathbed, Hungerfield grapples with Death until the reaper flees, but the family soon learns to mourn the act. This is followed by a poetic dramatic adaptation of Euripides' Hippolytus, retitled The Cretan Woman. A set of shorter - but not necessarily lesser - poems round out the collection.

Throughout, Jeffers is haunted by death, but the specter is understood and accepted as a part of nature which cannot be evaded without consequences. Indeed, the author seems to find it easier to accept death than its

... sister named Life, an opulent treacherous woman,

Blonde and a harlot, a great promiser,

and very cruel too.

and very cruel too.

His poetry is full of vivid descriptions of nature,

... the enormous unhuman beauty of things; rock, sea and stars, fool-proof and permanent,

which Jeffers loves rather more than he loves human beings, though

Humanity has its lesser beauty, impure and painful; we have to harden our hearts to bear it.

Much of his poetry mocks at man and his illusions of self-importance, his pretence of mastery. As The Cretan Woman prophetically concludes

In future days men will become so powerful

That they seem to control the heavens and the earth,

They seem to understand the stars and all science -

Let them beware. Something is lurking hidden.

There is always a knife in the flowers. There is always a lion just beyond the firelight.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)